British Oil Paints in the Age of Empire: Charles Roberson’s Media Climates

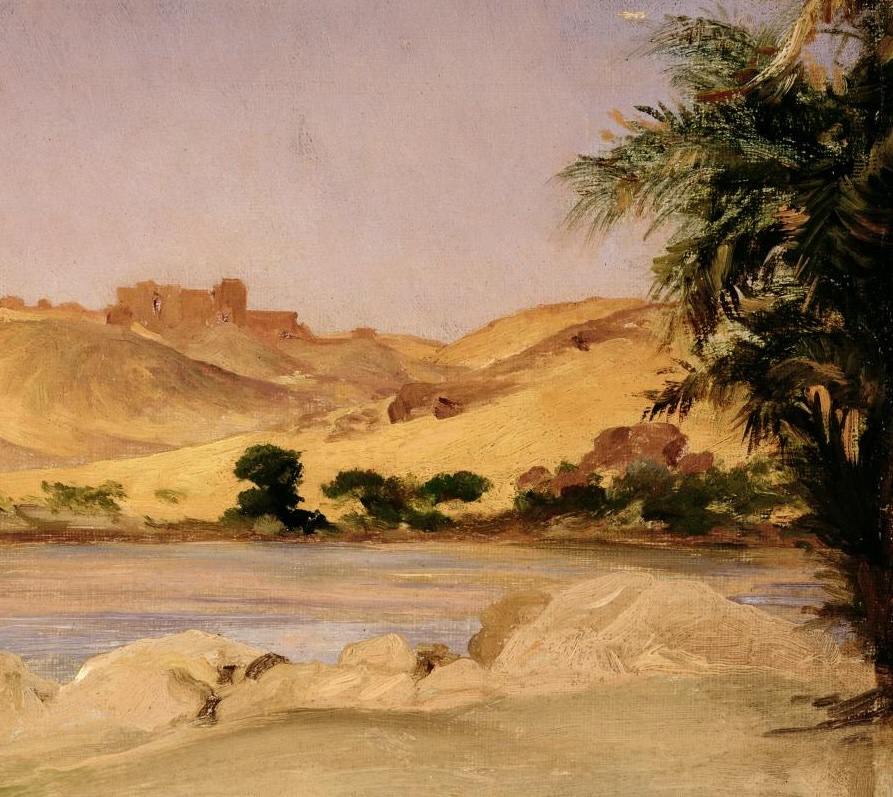

This paper focuses on the British artists’ supplier Charles Roberson (established 1820), to consider how the physical demands of making art in the diverse climates of the British Empire forged new material and technical practices for British painters of the nineteenth century. When pigments, oils, and mediums had to withstand long journeys and operate in varied climates—from the freezing temperatures of Antarctica to the tropical atmosphere of the Caribbean—how did this shape the way materials were made in the metropole, and what impact did the transformed physical nature of these materials have upon artistic practice? How did the new texture, consistency, chemical composition, and packaging of paint enable new kinds of aesthetic and technical experimentation? Roberson, one of the most significant colourmen of nineteenth-century Britain, supplied oil paints and its famed “medium” for use in a host of climates, from Frederic Leighton’s travels across north Africa and southwest Asia to Sir Ernest Shackleton’s expeditions to the South Pole. Here, I explore how Roberson adapted these materials to varied environmental conditions and ask in turn whether this enabled new technical experimentations in the handling and application of paint by the firm’s other domestic customers, which included John Singer Sargeant and Walter Sickert. Examining colonial modernity to be a techno-material, as well as an ideological, paradigm in British art, this paper considers how Empire shaped the making as well as the meaning of art in the nineteenth century.

Biography

Kirsty Sinclair Dootson is Lecturer in Film and Media at University College London. Her work explores the material and technical histories of modern visual media, particularly in British and British imperial contexts of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her first book The Rainbow’s Gravity: Colour, Materiality and British Modernity (Paul Mellon Centre/Yale, 2023), revealed how new chromatic media changed the way Britain saw itself and its Empire between 1856 and 1968. The book received the Modernist Studies Association First Book Prize and the British Association of Film, Television, and Screen Studies Best First Monograph Award. Her research has been supported with grants and fellowships from The Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, The Yale Center for British Art, Historians of British Art, The Huntington Library, The Association of Print Scholars, and The British Association for Victorian Studies among others.